Chapter three in Milkwood is all about Natural Beekeeping, and how you can use a principles-based approach to keep bees at home, safe and well, in a range of hive designs.

But why natural beekeeping? Why not just keep bees in the ‘normal’ way? Well, from our perspective, and the perspective of a growing number of natural beekeepers worldwide, for some very good reasons….

“…The future for honeybees is uncertain. Between various bee diseases that have spread worldwide, environmental pesticide use, mismanagement and habitat loss, bee populations in many parts of the world are strung-out and struggling. Keeping bees on a small scale in a naturally bee-centric way with minimal intervention, and putting colony health first before a honey yield, can help greatly.

As Simon Buxton, beekeeper and author, said, ‘The future of bees is not in one beekeeper with 60,000 hives, but with 60,000 people keeping one hive each…’

The hive in its natural state

When wild bees are seeking a new home, they’ll look for a protected space with a small entranceway and a large, preferably well-insulated, internal cavity. Often this is a tree hollow or a rock crevice, but it can be anything from a letterbox to a roof cavity. The bees will work with what they can find.

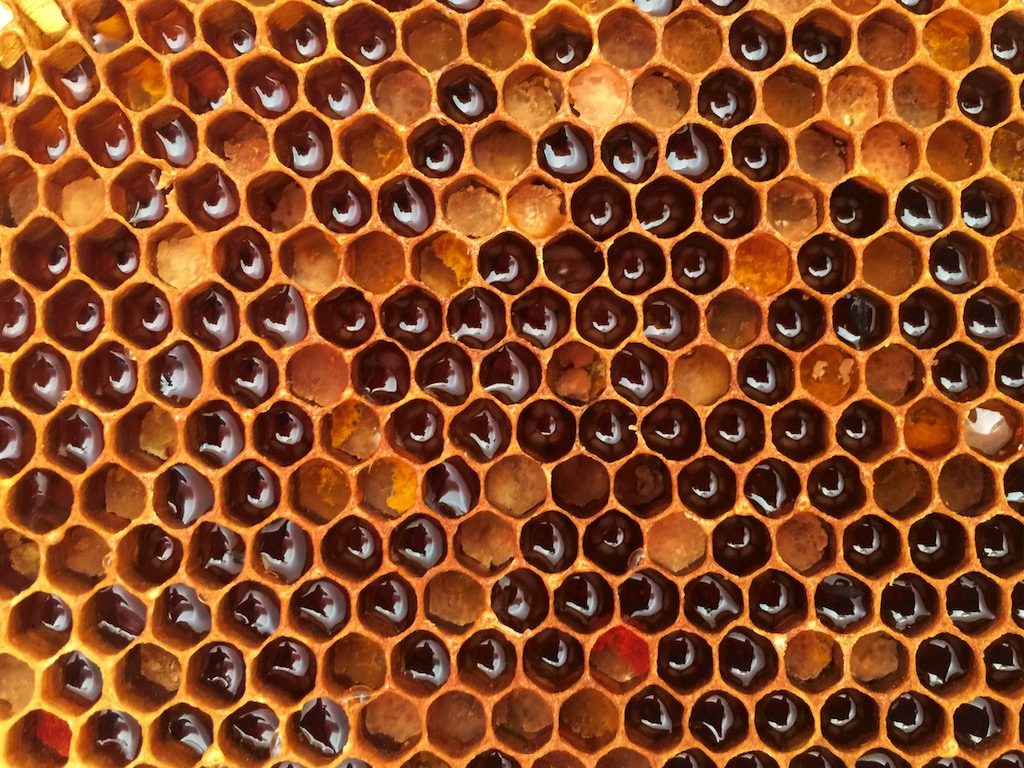

In a typical tree hollow, the bees will first clean out all undesirable material. They will then proceed to start drawing long, vertical comb from the top of the cavity for their queen to lay into, storing honey around the central ‘brood nest’ of cells containing baby bees. They plug and cover the walls of the cavity with propolis, an antibacterial and highly medicinal substance that they make from collected tree resins.

When the bees feel a comb is getting too big to be stable, it will be cross-braced in whatever way they see fit, which creates the amazing crenelated patterns we see in wild comb hives. Holes and peripheral galleries are created wherever needed to allow movement between combs.

As the queen lays successive generations of brood, each one below the previous generation, the generation in the cells above hatches. Once each newly hatched bee vacates its cell, that cell is immediately packed with pollen to support and feed the brood below. When that pollen is eaten, the cell is packed with honey and then capped. In this way, the pattern continues – a descending brood nest enclosed by a wreath of pollen, topped by a growing dome of capped honey.

The bees will continue this pattern until the end of the season, when it becomes too cold to fly. They then stay inside the hive, tending the remaining brood, eating their honey stores and keeping their core temperature stable until spring. In warmer climates, honeybees may not go broodless nor stop flying over winter, but instead maintain a smaller brood, which expands again in spring.

Natural Beekeeping: a bee-centric approach

Simply put, natural beekeeping is the practice of managing a bee colony as a whole, in a tree hollow or, more often, a simulated tree hollow.

The term ‘natural beekeeping’ is, however, an oxymoron in some ways – in the same way that ‘keeping’ any wild thing is. The act of hands-on stewardship means that the organism (or super-organism) is no longer completely wild or in its natural state.

Honeybees are wild creatures in a super-organism form. They are neither pets nor livestock. Unless disabled or prevented, they will do as they choose, each and every time. The trick to natural beekeeping is learning to work with the bees for a mutually excellent result.

So the term ‘natural beekeeping’ is really a term of comparison. In relation to conventional beekeeping practice, in which the hive design and management techniques are aimed at maximising honey harvest for the beekeeper, the super-organism of the bee colony is broken into pieces, and cannot operate as a whole. Natural beekeeping, which keeps the super-organism intact, aims to put the bees needs first, and honey harvests second.

There are many beekeeping traditions across the world that strive to keep bees in a way that honours and respects their wildness and keeps the colony intact, while still enabling a honey harvest. And harvesting is really the crux of the issue here – finding a way, through good hive design and management, to harvest with minimal disturbance or manipulation of the colony. In this way, the bees can live on, from year to year, happy and healthy in the space we’ve provided for it.

Choosing a hive design…

As a beginner beekeeper, it’s very easy to get confused about different hive designs, management techniques, plastic inserts, taps, queen excluders and all the rest.

If you’re interested in keeping bees in a way that puts the bees’ needs first (which doesn’t necessarily mean a lessened harvest, because healthy bees are productive bees), start by doing a bit of research, and consider a principles-based approach.

Natural beekeeping principles encompass the basics of what bees need to thrive, and so they’re excellent principles to guide a beginner natural beekeeper. With proper care and attention, these principles can be applied to a range of different hive designs.

Some hives used in natural beekeeping are box hives, kept in a vertical stacked format. There are also various horizontal hives that mimic a horizontal tree hollow. And there are actual log hives, and neo-skep hives… and so many others. For the purposes of this book, we’ve used the Warré hive (the one made by the French monk Emile Warré) as the default hive design. It’s a vertical box hive that has top bars in each box. There’s a rundown of this hive design on pages 148–149.

Once you get your head around the fundamentals of what bees need to be healthy, you can make your choices accordingly, and get hold of (or make) a hive and gear that’s right for you, your context and the bees.

Natural Beekeeping Principles

These principles can be applied to a range of countries and contexts. They include the essentials of what a honeybee colony needs to thrive and create long-term resilience for bees as a species, and for us, too.

Natural comb

Allowing bees to build their own comb is essential for long-term colony health. Natural comb is literally made of bee. The bees secrete flakes of wax from the underside of their abdomens and then shape it into cells in a collective construction operation, and these cells are then used successively to harbour babies, pollen and honey. Classed as part of the super-organism, the comb is the bees’ womb, home and larder. The bees vary their comb’s cell size according to their needs (drone cells need to be bigger, for example), and draw comb at different speeds and sizes, according to the season’s attributes.

By drawing their own comb, rather than being forced to use plastic, pre- made or re-used comb, the bees can ensure that the queen is always laying into fresh, virgin comb, which makes a big difference to colony health. The wax comb is lipophilic, and like the fat stores of any organism, accumulates any toxins that the bees come into contact with, building up over time as the bees work that comb. This is part of the reason that comb renewal is so important.

Comb renewal

Comb renewal happens naturally in a wild hive. When the bees deem a comb to be old or contaminated, they will cut it out and either dump it at the bottom of the cavity or fly it out the front of the hive and drop it there. In conventional beekeeping, the bees don’t have this option. They’re stuck with the fixed comb they’re given, and must re-use it as many times as the beekeeper sees fit – both for brood and honey storage.

In natural beekeeping, facilitating comb renewal is paramount. Having your bees cycle through fresh comb cleanses the hive, drastically limits toxin build-up (both for the baby bees and in the honey that you eat) and means the hive is as healthy as it can be, even in the face of widespread environmental chemical use.

Comb renewal can be helped along by providing ongoing space beneath the colony, allowing the bees to continue to draw new comb downwards. This beekeeping process is called ‘nadiring’ – placing an empty hive box under the existing colony, which gives the colony space to grow with minimal disruption. In this way, the colony can draw comb endlessly downwards. And excess honey can be harvested periodically from the top box, at the top of the honey dome, with minimal disturbance to the hive.

The comb renewal process is also helped along by the fact that in natural beekeeping, the whole honeycomb is harvested – this ‘flushing’ effect further limits disease and toxin build-up, as no old comb is returned to the hive.

Natural reproduction: swarming and re-queening

In terms of a honeybee colony, natural reproduction happens on two levels. The first is reproduction of the super-organism as a whole, when the colony splits via swarming. Swarming is an optimistic act in which a colony chooses to split in half to reproduce itself. The existing queen flies out with the swarm, while a portion of the colony stays behind with a new queen. Often bees will swarm if environmental indicators point to a good season ahead. Sometimes a hive will swarm because it has completely run out of space in its hive cavity. This allows the halved colony that’s left behind to rebuild its numbers.

The second form of natural reproduction is on an individual level, allowing the bees to raise a new queen when they choose and allowing that queen to freely mate with local drones. A honeybee colony may decide to raise a new queen because the existing queen is old, sick or injured, or laying poorly. When this happens the bees will change the diet of a chosen egg or eggs to create potential new queens.

Allowing bees to swarm and/or raise their own queens means that the hive itself chooses the next queen. They choose the timing of when she is produced and, importantly, her genetics. In the process of conventional ‘re-queening’, a commercially produced queen bee is typically mail-ordered and then added to the hive. This queen will usually be bred to focus on various traits – e.g. golden colour, quietness and honey production, traits favoured by commercial beekeepers. In a natural beekeeping system, however, there are other important traits that are valued in a queen and the genetics that she passes on – local disease resistance, strong comb-building abilities, strong foraging and successful swarming abilities, to name just a few. Natural, locally adapted genetics are vital to ongoing colony health. The bees know what they need. Let them decide and reproduce accordingly.

Natural reproduction is important not just for individual colonies but also for the ‘super-super-organism’ that is the community of bees in a given area, all interacting and swapping locally adapted, resilient genetics to ensure long-term colony health for all.

Natural food: honey and pollen

Bees eat honey and pollen. These are both food and medicine to them, and represent a complete diet throughout an adult bee’s life.

The thousands of species of beneficial microflora found in both honey and bee bread are largely a result of the honey-making process. As the bees eat and regurgitate the nectar many times between its arrival at the hive and its eventual packing into a cell, layers and layers of microflora are introduced. By the time the nectar becomes honey, it is a serious probiotic powerhouse and the perfect food for bees.

The pollen that bees collect in baskets on their legs from millions of flowers is similarly processed inside the hive, becoming ‘bee bread’. This is stored in cells both to feed baby bees and to provide protein for adult bees as well. It’s another dense food and medicine for the bees, containing many species of microflora.

When you understand what honey means to bees, it’s pretty easy to see why it’s so important to ensure they have the food they need, especially through cold winter months, for optimal colony health. Beekeeping practices that harvest too much of the honey from hives over the summer create a situation where the bees do not have enough stored food to make it through the winter. It is then common to feed the bees on sugar water. It’s a bit like us living on white bread alone for six months. Instead of a wholesome, balanced diet, sugar water provides empty carbohydrates with none of the probiotics or medicinal aspects of honey that bees need, especially when they are stressed, cold or sick.

In natural beekeeping it’s essential to ensure the bees have enough honey stores at all times. In a crisis, feeding starving bees clean honey, preferably in the form of honeycomb and always from a disease-free hive, is the best substitute for their own honey stores.

Minimal intervention

A minimal intervention approach towards beekeeping limits hive opening and disturbance of the colony. Minimising intervention doesn’t mean ignoring your hive, however. If anything, your relationship with the hive is enhanced and more nuanced.

Since a bee colony is a warmth organism, maintaining the colony’s internal heat is crucial. Bees are not warm-blooded by themselves, so they create this collective heat through friction. Heater bees buzz their bodies at a frenzied rate, generating heat for the benefit of the colony and the health of both brood and adults. Along with the ‘nest scent’ (the environment of pheromones actively used for communication within the hive), maintaining this core temperature is intrinsic to colony health and disease suppression. Limiting the times you open the hive from the top to two to three times per season is a big help in retaining this heat and scent.

Another way to check on the bees throughout the season is to observe the entrance activity. Bees bringing in pollen means the queen is laying well. Bees flying in low and crashing onto the bottom board (or below it, and crawling up) can mean that there is plenty of nectar around and the bees are coming back fuller than full. Bees landing light on the bottom board can mean that nectar foraging is sparse. Different smells also indicate different things. Read the signs (and good books on the subject) and you will learn a lot from what happens at the hive entrance.

Nadiring is yet another way to minimise intervention. Until a hive is many boxes high, getting a friend to help raise the hive as a whole and slip a box underneath is a great low-intervention way to add space to the hive without opening it up.

Natural management

In an age where bees on many continents are routinely dosed with chemical treatments, either to control existing disease or in anticipation of infection, the idea of natural management flies in the face of much conventional beekeeping practice. However, a dedicated focus on good hive management, natural husbandry and disease prevention are key to healthy bees, in the same way that these techniques are key to growing healthy food or keeping healthy animals.

The principles outlined above, particularly ensuring natural comb renewal and natural reproduction, have been shown to greatly lessen bee colony diseases over time. With lots of research and careful observation, good management and prevention can be your key tools for hive health…”

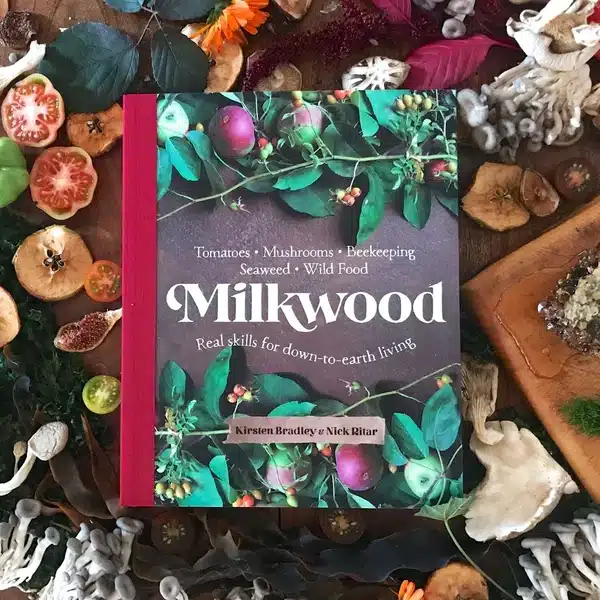

The above is an extract from the Natural Beekeeping chapter of our new book Milkwood – real skills for down to earth living.

If you’re keen to learn more about stewarding bees (or foraging seaweed, growing tomatoes, finding wild food or mushroom growing), you can buy a signed copy from us or pick up a copy at your local bookshop.

Our Natural Beekeeping chapter references:

Bee biology: The Biology of the Honey Bee, by Mark L. Winston. Harvard University Press, 1991 / The Buzz about Bees: Biology of a Superorganism, by Jürgen Tautz. Springer, 2009 / Honeybee Democracy, by Thomas D. Seeley. Princeton University Press, 2010 / The Wisdom of the Hive: The Social Physiology of Honey Bee Colonies, by Thomas D. Seeley. Harvard University Press, 1996 / The Dancing Bees, by Karl von Frisch. Harcourt Brace, 1953.

Warré beekeeping: Natural Beekeeping with the Warré Hive, by David Heaf. Northern Bee Books, 2013 / Beekeeping for All, by Emile Warré. Northern Bee Books, 2010 (English translation) / Tim Malfroy’s Natural Beekeeping website: naturalbeekeeping.com.au / David Heaf ’s Warré resources and online forum: warre. biobees.com

Natural beekeeping: The Bee-friendly Beekeeper: A sustainable approach, by David Heaf. Northern Bee Books, 2015 / Wisdom of the Bees, by Erik Berrevoets. SteinerBooks, 2009 / Top-Bar Beekeeping: Organic Practices for Honeybee Health, by Les Crowder and Heather Harrell. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2012 / The Barefoot Beekeeper, by Philip Chandler. Lulu.com, 2008 / Natural Bee Husbandry Magazine – ongoing.

History of bees and beekeeping: The World History of Beekeeping and Honey Hunting, by Eva Crane. Routledge, 1999 / A Book of Honey, by Eva Crane. Scribner, 1980 / The Sacred Bee in Ancient Times and Folklore, by Hilda M. Ransome, Dover Publications, 2004.

Making mead: Make Mead Like a Viking: Traditional Techniques for Brewing Natural, Wild-Fermented, Honey-Based Wines and Beers, by Jereme Zimmerman. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2015 / The Wildcrafting Brewer, by Pascal Baudar

All our articles about Natural Beekeeping are here.

Hello, this is a fabulous article. I have done Tims course and keep bees in Warre Hives. I am also President of The Orange Beekeepers and editor of our monthly newsletter. Would it be possible to use this article, with appropriate acknowledgment, in our next newsletter.

Regards Cameron Wild

Hi Cam! And of course, go for it – it’s a snippet from our Natural Beekeeping chapter of the Milkwood book 🙂

My favourite Beekeeping book is: The Idle Beekeeper (referring to minimal intervention) by Bill Anderson.Have a look.

Yes! Love that one 🙂

Fantastic article, thank you. Have inheritted a swarm that stayed under my patio for 9 months now homed in my first langstroth ? Hive. Wish I had seen the Warre hives earlier but really looking forwsrd to being a good steward to the crew.

Great (but also normal !) vision on (real) beekeeping !

Keep the good work up !

thanks!

Very informative article, I always believed the less disturbance is the best for honey bees… but there is very crucial misunderstanding: HONEY bees are NOT endengered – OTHER spicies of bees are the ones struggling – stingless bees, solitary bees like bumble bee, mason bee, etc.

Great article, @Kirsten!

My next thing I would like to learn and practice…

I HAD A SUPPLIER OF BEESWAX IN OHIO, I’M IN NY. HE SOLD ME WAX FROM HIS HIVES THAT WERREN’T EVER SPRAYED. DO YOU HAVE A CONTACT THAT SELLS BEESWAX FROM NATURAL HIVES? i’M MAKING PRODUCT BUT WILL ONLY USE PURE, CLEAN GOODS. NO SPRAYING OF THE HIVES. THANK YOU, FRANK B