http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oDXZc0tZe04

This is a great little video from Gaia Bees, an American natural beekeeper doing some very interesting work in bee colony resilience and apicentric beekeeping.

The super interesting thing about this video is that it clearly shows how, in a ‘wild hive’, the colony starts at the highest point of the cavity, and draws their comb downwards. This is precisely what Emile Warré was trying to mimic with the way his ‘people’s hive’ worked, and with his approach to beekeeping…

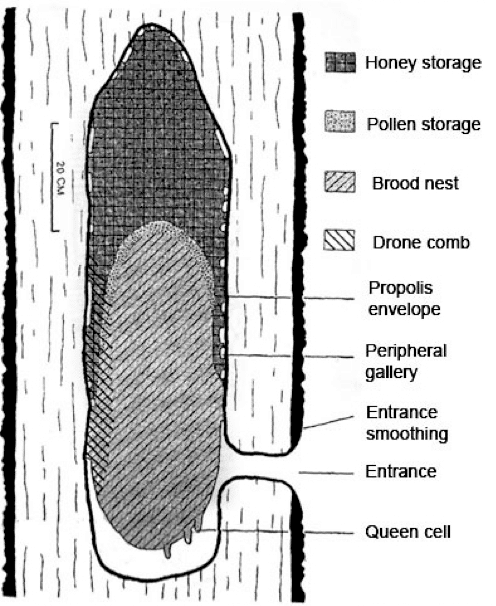

Typical composition of a wild honeybee hive

Another key thing that this video shows is how the bees cover the comb as they move down… in nature, bees don’t leave large amounts of empty space, or empty comb above them.

They build the comb, then fill it with brood (baby bees), and then as each successive generation of babies hatch, those empty cells above get filled with pollen and with honey.

All the while, the bees are building more comb down the cavity and repeating the above process.

In this way, the brood ‘nest’ slowly moves downward with each successive generation of eggs laid and hatched and tended, always with a dense thermal dome of honey and pollen above it.

With his ‘people’s hive’ Emile Warré was trying to create a hive that allows the beekeeper to mimic and allow for this natural behaviour, so as to make as bee-friendly a beekeeping system as possible.

While also getting a yield of honey, if the season is a good one.

Typical Warré hive construction, which aims to mimic a vertical log cavity while allowing for intermittent harvests when the season produces more than the bees need

The act of ‘nadiring’ is one of the Warré beekeeping techniques central to this process. Nadiring is the act of expanding the hive by placing empty boxes at the bottom of the colony, rather than on top. Extending the tree cavity below, as it were.

By allowing the bee colony to constantly draw new comb downwards, the brood is always protected from temperature fluctuations by a dense dome of honey and pollen directly above it.

This technique also means that new brood is always laid in fresh, just-made comb, which is far healthier for the colony as a whole, and for breaking disease vectors.

Nadiring also means that the beekeeper is never introducing blank, uninsulated space directly above the brood nest in the form of an empty box of frames.

This can lessen the overall stress of the colony dramatically, as the bees don’t have to frantically fill the suddenly introduced empty space above their babies with comb and honey stores to keep their brood nest healthy and temperature stable.

All these factors help minimise the stress of the bee colony, which in turn contributes to that colony’s overall health, and thus its ability to deal with disease, parasites, variable seasons and environmental toxicity.

A frame from a naturally managed Warré hive showing the pattern of brood, closely followed by pollen and capped honey stores above

All of this is somewhat at odds with conventional beekeeping technique, however, which restricts the brood to the bottom section of the hive (using a queen excluder so that she cannot climb up and lay in the boxes above) and introduces empty boxes on top of the colony regularly.

The effects of these practices on the colony are many, but include the queen laying multiple generations of brood in the same comb. The worker bees will also compulsively and continually fill the regularly renewed empty boxes / re-introduced comb (or ‘stickies’) above their brood nest to try and regulate the hive’s temperature.

This is a great way to maximise honey production, but is probably (to be gentle about it) not the best way to go about ensuring optimal colony health and resilience.

It’s interesting to me that as we sign every ‘save the bees’ petition that comes across our paths, but we are not, as a population, largely motivated (yet) by the idea of apicentric beekeeping – the idea of putting the health of the bee colony before it’s harvest.

I do think this will change, and like our approach to keeping many other species of animal for their life-giving outputs and harvests, it’s largely a matter of more of us understanding what’s going on here for the species involved.

Perhaps we need to place more importance on, as Joel Salatin puts it with his animal husbandry, the ‘pigness of the pig’ – in order to better farm that animal in an ethical, regenerative and companionable way.

Widespread understanding of the ‘bee-ness of the bee’ will have its day, I hope.

And I think we’re on our way there, because there’s plenty of great resources on the how and why of apicentric beekeeping already, with more cropping up all the time, as small scale beekeepers (who represent the future of beekeeping globally) keep observing and slowly forging a path ahead…

Natural comb in a Warré hive, closely attended by the colony…

Resources to start with:

- Honeybee Democracy & The Sacred Bee: two great bee books

- Bee Friendly: A planting guide for European honeybees and Australian native pollinators

- Natural Beekeeping Resources: best books

- Gaia Bees website

If you’re in Eastern Australia, come learn Natural Beekeeping using the Warré hive method with us! We run awesome courses that skill up api-centric beekeepers, taught by Tim Malfroy.

>> More posts and resources on Natural Beekeeping

Cheers to Tim Malfroy for the (ongoing) conversation on natural comb that led to this post.

Great video and post. I have been contimplating having bees on my hobby farm north of Perth. Thanks for some great information and for givinge some motivation. Keep up the great blog.

Hi! I love the Warré style of beekeeping and how it tries to keep the bees as naturally as possible. I had bees for a year and a half, using a Warré hive, but after we moved I haven’t had bees again. I want to start beekeeping again next year and have had second thoughts about Warré and if maybe I shouldn’t rather use a topbar hive. (Maybe I’ll try both.) My main concern about the Warré hive was as follows and I’m curious how you deal with it as I don’t know any other Warré beekeepers: When nadiring you… Read more »

Warre boxes are a lot smaller that Langstroph supers at 300mm x 300mm x 210mm high and therefore do not weigh as much. If you go on the Warre websites you will be various lifting mechanisms that have been designed. It is also OK to take individual boxes off one at a time, nadire the empty box on the bottom position and replace the boxes one by one in the same order.

Thanks for posting, just lovely watching those bees do their stuff, think we will give this a go on our small acerage in NSW…. just to have bees around, only question, how to set up the log so that a swarm comes – anything that you can do to entice them?

Yes definitely cheers to Tim Malfroy and to Milkwood. A constant source of information, and whoever does the website is to be saluted.. I salute you 🙂 love the bright, colouful design and the drawings.

We at northcotecommunitygardens.blogspot.com, are building a Kenyan topbar hive at present. We are nearly there, and then next year, I am hoping to pursuade the mob to try a Warre hive next.

Many thanks for your work, it has kept me learning, enjoying and marvelling a lot. eg. the Alan Savory video.

marijka

Waw, that ‘s an amazing piece of footage! Good on the thinker in coming up with this technique to monitor hive development. Astonished!

When the comb is removed from the hive to remove the honey, does this destroy the hive? Do the bees then make a new one? Or does it just mean they have to rebuild the top bit and fill it up with honey again? If the Queen isn’t forced to stay in the bottom bit and only lay eggs there, what effect does this have? Is this what reduces the amount of honey produced? I think the bees health should be put over their honey production, but if this is done do they still make more honey than they need… Read more »

I love bees!……such busy little things……the unsung heros of our planet!