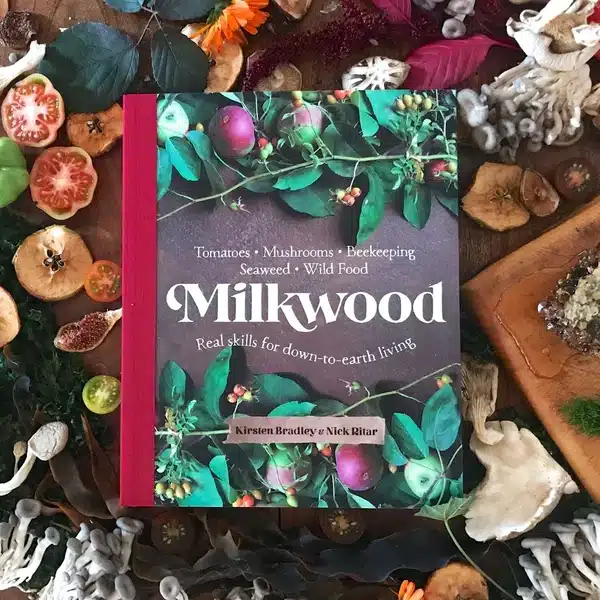

Here’s a little extract from chapter 1 (The Tomato) from our first book, Milkwood…

We can’t quite imagine life without tomatoes. They’re such a large part of our lives in spring, summer and autumn, and in winter, too.

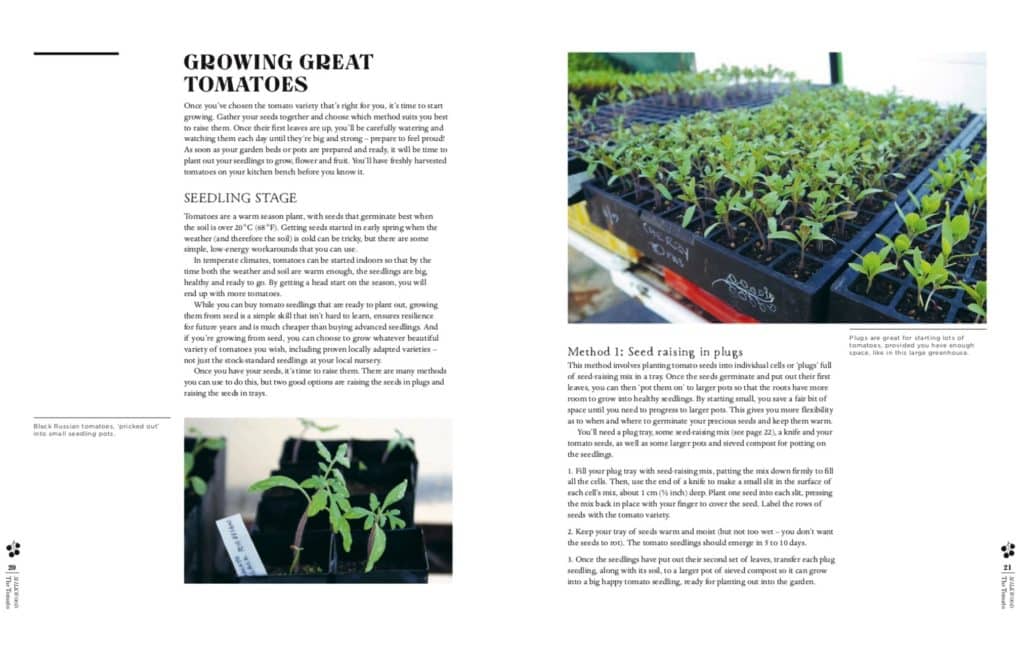

First, the careful seed-raising stage in early spring, in the warmth of our kitchen and then our greenhouse, as we watch closely until the first green leaves emerge. Then the potting on, and all the careful stewarding and watering through the cold snaps of spring until the seedlings are huge and it’s finally time to plant them out.

And then over summer the growing, and the care, and the trellising, and the feeding… and then on to the harvesting and all that autumn tomato eating. Over late autumn, winter and spring, tomatoes are central to our home kitchen in the form of bottled passata, chutneys, preserves and dried tomatoes.

Tomatoes are the memory of summer that we hold onto on a rain-whipped, frozen-fingered evening of chores done in the dark of midwinter, when we’re sure that we’ll never be properly warm, ever again. We thaw out by the fire with a steaming bowl of tomato-based stew in our hands – home-made and heartfelt.

And then the days lengthen, and before we know it we’re choosing which tomato varieties to plant, the seeds carefully stored last autumn for just this moment!

The Troubled History of the Tomato

Tomatoes belong to the plant genus Solanum, and are cousins to potatoes, eggplants (aubergines) and the rest of the nightshade family. Like the potato, the tomato originated in the Andes of South America. Cultivated and eaten extensively by the Aztecs, who called them ‘xitomatl’ (fat water with navel), tomatoes started off as a predominantly yellow fruit. They had a fabulous ability to quickly mutate into other colours and forms, adapting to any new climate that had enough light and heat to support their growth.

The Spanish invasion of Mexico saw the tomato – an exotic, plump fruit with a wonderful scrambling vine – travel to Europe in the 1500s. It was met with some reluctance due to its similarity to other poisonous nightshade plants. The Spanish soon incorporated the tomato into their cuisine, but the Italians grew tomatoes primarily as ornamentals, using the fruit as a table decoration for some centuries before it became part of their food tradition.

The Latin name for tomato, Solanum lycopersicum (wolf peach) harks back to the tomato’s close association with deadly nightshade. In the 1600s, everyone in Europe knew that deadly nightshade was the food that witches used to turn themselves into werewolves. Clearly the tomato was a bit more peachy-looking than the small black berries of deadly nightshade, but it was still suspicious.

The tomato made its way to the Middle East via Aleppo in the late 1700s. It then travelled to Africa, where it was quickly embraced into many cuisines that already featured eggplant, the tomato’s cousin. The tomato travelled back to North America and to the Caribbean from Europe in the 1700s and became an established crop in the USA by the 1800s.

Declared ‘unfit for eating’ in an early British herbal, Britain nevertheless took ‘love apples’ into its cuisine in the 1800s, while still growing them widely as a summer ornamental.

The story of the tomato is a curious one because it is such an important ingredient in so many national cuisines. It’s difficult to imagine Moroccan, Spanish or Italian food without the sweet lovin’ that tomatoes bring. So it’s strange to consider that the tomato effectively made the leap from a relatively unheard of, werewolf-inducing love apple to a deeply beloved ingredient – to the point of national patriotism – in just over two generations.

For us, there’s no summer without tomatoes. And the first ripe, home- grown tomato of the season – filled with warm sunshine and all the care and anticipation that has gone into its arrival – is one of our very favourite things in the world.

Our Best-Ever Seed Raising Mix

Getting your seed-raising mix right is important for growing strong seedlings. Making your own is much cheaper and usually assures a higher-quality mix than using a commercial seed-raising mix.

While you can buy mixes from the shops, making your own is much cheaper and usually assures a higher-quality result than a commercial seed-raising mix.

Growing Great Tomatoes

Once you’ve chosen the tomato variety that’s right for you, it’s time to start growing. Gather your seeds together and choose which method suits you best to raise them…

Here’s a few tomato-raising tips from our new book Milkwood‘s The Tomato chapter (click to enlarge the images below)…

Welcome to spring, southern friends! We thought, in light of warmer days ahead, that you might appreciate some tomato growing tips.

The tomato chapter of our book covers everything from tomato history to growing from seed, planning beds, planting, caring, pruning, companion planting, and harvesting, as well as what to do with your tomato bounty later in the season.

And remember that even if you can’t grow tomatoes due to a lack of space, that does NOT leave you out of our tomato appreciation society.

No matter where you live, you can organise to get a box of red-ripe tomatoes from your local grocer (or even better, your fave farmer at your local farmer’s market) for later in the season. Then gather your friends, and get passata making and/or preserving and ketchup making, with some fermented salsa on the side Because life is better together. And with tomatoes.

Everything you need to know to get growing and making for year-round tomato goodness is in our book.

Enjoy, feel free to share, and let us know how you go?

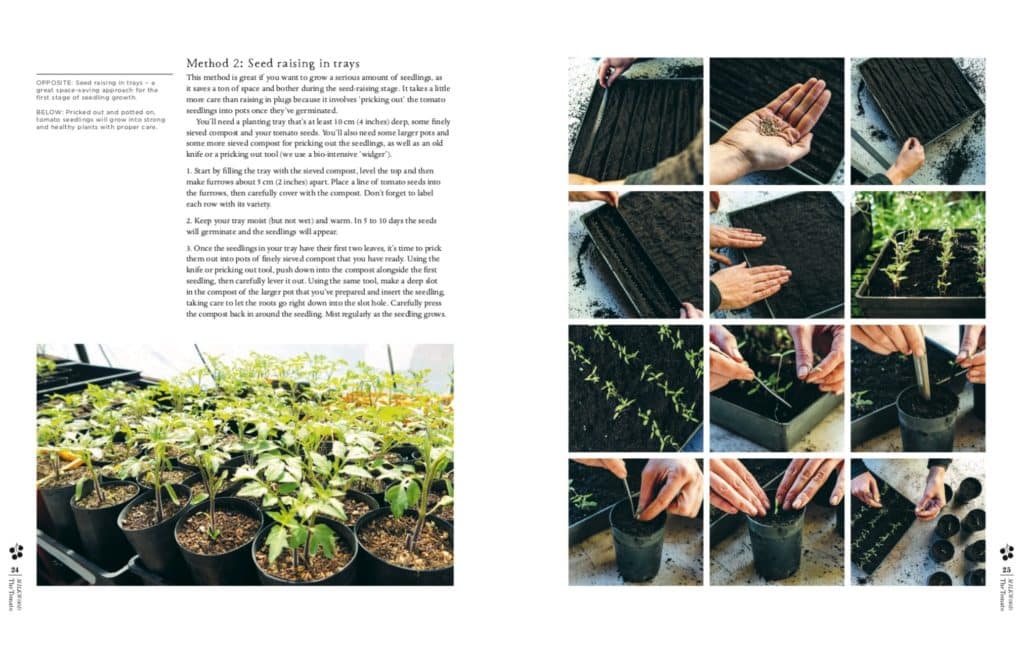

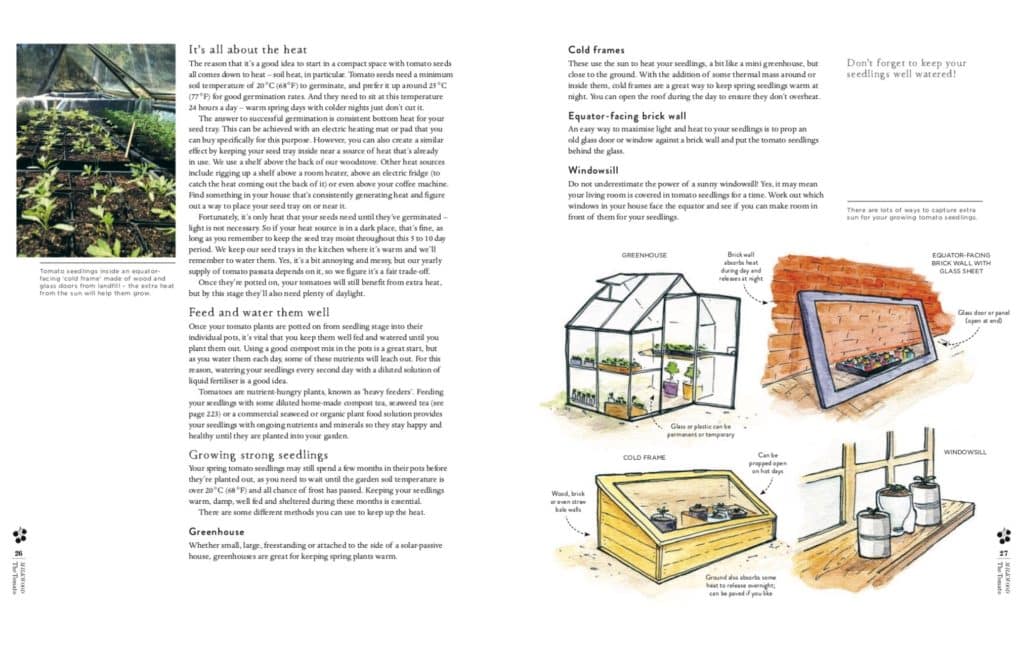

All the pics above are from The Tomato chapter of Milkwood, taken by Kate Berry (well all the good photos above, anyway). Brenna Quinlan did the illustrations, and Milkwood is published by Murdoch Books.

love your (hard) work, so inspiring, just a small add, mine were always behind the tomato seedlings I saw around me until I realised they sow the seed in July August, this is early but if you need to extend the season as I do in Ballarat (cold district) early sowing is imperative.